Can Coyote Contests Improve Deer Survival?

By Gerry Lavigne

People who sponsor and participate in coyote contests do so believing they can improve deer survival by reducing coyote populations. But can they? Research in Maine has demonstrated that predation by coyotes can negatively impact deer populations, particularly in the northern half of the state. Venison is a large portion of coyote diets during winter, and along with bears, coyotes target newborn fawns during early summer. Logically then, if hunters and trappers can reduce coyote populations during winter and early spring, they could conceivably improve deer survival.

Improved survival of deer would lead to population increases and potentially make more deer available for hunter harvests. That’s a lot of “ifs”. To be effective at reducing coyote populations, contests would need to focus on a discrete area rather than removing individual coyotes just here and there over a wide area. Can they do this?

In 2010, I monitored a contest operated out of Mack’s Trading Post in Houlton. I was able to get a list of participants and where they hunted. That year, 84 coyotes were killed from an area of approximately 600 sq. mi. Based on the DIFW’s estimate of winter population density, these hunters removed roughly 30% of the coyotes in this 600 sq. mi. area. In my view, that is a significant reduction, especially considering this does not include the coyotes which were taken by trapping or hunted by people who were not in the contest.

There is another thing to consider. In the northern half of Maine, most successful bait hunters and callers focus on locations within a few miles or less of deer wintering areas. That’s simply where most coyotes are during winter. So, contest participants are in effect targeting the deer killers, not the bunny and mouse killers in the coyote population. Reducing these coyote packs will increase the likelihood of improving deer survival. There are 2 long-running (16-year) coyote contests in Maine, one of which has enough data to test whether targeted coyote hunting translates into improved deer hunting.

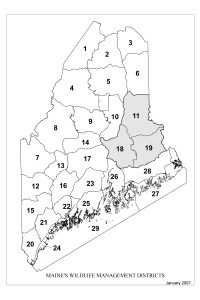

The Penobscot County Wildlife Conservation Association’s (PCWCA) coyote contest has been an annual winter event since 2010. Ground zero for this contest is Smith’s General Store in Springfield, ME. However, participants can now enter their coyotes at three other locations: Lincoln, Waite, and Grand Lake Stream. With few exceptions, PCWCA’s contestants operate in Wildlife Management Districts (WMDs) 11, 18, and 19 in east-central Maine (see Map). PCWCA’s coyote contest spans December 16 to March 31 annually. Participants pay an entry fee, and they must register and weigh all coyotes killed at one of the four tagging stations. All entrants must be legally licensed hunters, and there are safeguards in place to prevent double tagging of coyotes presented for weighing. In addition to entry fees, contest organizers solicit funds from area businesses, and there is also a raffle to generate revenue. Contest funds are pooled, and a $200 prize is awarded for the largest male and female coyote entered. Another $200 is awarded in a random drawing. The remaining funds are awarded for each coyote entered in the contest. In essence, this is a private bounty.

These rules provide a financial incentive for participants to kill and enter all the coyotes they can, large or small, male and female. Hence, the coyotes recorded in this contest are probably an accurate representation of the coyote population in these WMDs. Over the years, the number of participants has averaged 59 but they varied from 33 to 104. Slightly less than half of the participants killed one or more coyotes in any given year. Successful participants averaged 5.6 coyotes each over the years, although a few killed 20 to 40+ coyotes each year. The bounty payout per coyote killed has averaged $23. The number of coyotes entered in PCWCA’s contest over the past 15 years averaged 149 but has ranged from 80 to 255 (see Table).

There is a definite trend toward increasing numbers of coyotes killed over the course of these 16 annual contests. The accompanying table also shows the number of deer tagged at Smith’s General Store in Springfield since 2005. For the five years prior to PCWCA’s contest, an average of 74 deer were tagged at Smith’s Store (range of 50 to 93 deer). The first three years of the coyote contest (2010 to 2012) saw no improvement in the number of deer tagged at Smith’s (49 to 68 deer). But then, things started to change. From 2013 to 2021 deer tagging at Smith’s jumped to an average of 117 and ranged from 96 to 141 over this 9-year stretch. More recently (2022 to 2024), Smith’s tagging records vaulted to an average of 162 deer (range of 157 to 165 deer).

Was it coincidence that the number of coyotes entered into PCWCA’s contest (range of 232 to 255) had vaulted by more than 100 coyotes per year compared to the previous 12 contest years? In 2025, another 223 coyotes were logged in at PCWCA’s annual contest. Will Smith General Store’s deer tagging records reach 160 or more again this fall? I can’t wait to see! Now here’s where it gets interesting.

When you plot the number of coyotes entered into PCWCA’s contest vs the number of deer tagged at Smith’s Store each year (see Chart), the correlation (r2=.68) between the two sets of data becomes very clear. Kill more coyotes; get more deer in the local harvest. The trend line in this chart is highly significant statistically (p<.01). In other words, it is highly unlikely that the increase in deer harvest with increasing numbers of coyotes killed is due to coincidence alone. The chart suggests that killing 100 or fewer coyotes in this area can have mixed results on subsequent deer harvest. But the relationship becomes increasingly stronger when the coyote kill reaches about 150 and beyond. To be fair, correlation does not prove causation.

To prove that targeted coyote removal improves deer survival and available deer harvest one would have to conduct intensive research on the two key players over a large area. And DIFW has no intention of doing so. Could other factors explain the increase in deer tagged at Smith’s Store over the past 16 years? Perhaps, but to a limited degree. For example, the past few winters have been mild in Maine compared to past winters. However, winters in this area are rarely severe enough to cause high starvation losses. Coyote predation far exceeds starvation losses among deer in WMDs 11, 18, and 19.

Could there have been a major change in the number of antlerless deer harvested during this period? No. Very few antlerless deer are allowed to be harvested in these WMDs compared to WMDs to the south and west in Maine. Although Smith’s tagging station’s tallies available to me showed only the total number of deer tagged, the overwhelming majority of deer tagged were antlered bucks. Could hunter effort or hunting weather explain the increase in deer harvest tallied at Smith’s? Not likely. The evidence is compelling: Intensive, targeted, and sustained removal of coyotes in this area has led to higher deer survival, at least in the area served by Smith’s Store deer tagging station. This result is not unique to Maine. There are several studies published in scientific journals that demonstrate an improvement in survival of mule and white-tailed deer, as well as antelope, fawns in the western US, when coyotes are intensively removed on a sustained basis.

In fact, numerous ranches employ professional coyote hunters/trappers to keep coyote numbers in check to minimize predation losses of lambs and calves. The key to success in all these cases is intensive removal to reduce coyote numbers at a critical time of year, along with sustained efforts every year to prevent repopulation of the area by dispersing coyotes seeking to fill the void. As I pointed out in an earlier article, properly managed coyote contests are a valid deer management tool, one which should be encouraged, not disparaged by state wildlife managers.

This legislative session, the antis sought to ban coyote contests in Maine. Fortunately, the Legislative Committee on Inland Fisheries and Wildlife saw the value of these contests in protecting deer. The bill failed to pass.

For more articles about hunting, fishing and the great outdoors, be sure to subscribe to the Northwoods Sporting Journal.