The Phantom Salmon of Fording Rock

Simmering, I handed the rod over to the one-armed man. “Go ahead, old codger,”

I said to myself, “show me something.”

The number twelve WhiteWulff fluttered in the air and settled as milk down on the center riffle of Landing Pool. Grandfather’s amber Edwards’ Quadrate was poised. Three feet of mended drift brought the expected result, an explosion of foam and a distended tear-shaped eddy. Again the fish had struck. Grandfather reeled in, exhaling.

“Well, that’s it for today. He strikes once.. .doesn’t really take the fly. It’s a big fish, Gif, but I don’t think he’ll stay here much longer; everyday for a week now he’s hit in the same lie a White Wulff.”

In 1957 I was thirteen, a barely weaned fly fisherman for three years. Under Grandfather’s tutelage I learned to cast as his father had taught him: “Think of a clock.. keep your arm tucked in.” As yet I had not caught a keeper salmon and my trout successes were ample but dollar lengthed. So I wanted to try for what Gramp called the “phantom salmon,” but he wisely said I was not ready. I wondered, though, why he couldn’t hook the fish and when the phantom would, as elusively as it appeared each day for a White Wulff, vanish like a ghost in a fog.

As we crossed the green single-spanned bridge over the Magalloway, I looked downstream at the Landing Pool. The river here was wide, maybe thirty yards and riffly. On the right bank from which we fished was the crib work where trucks would back up and loggers would chuck pulp into the river, a flotilla headed for the Brown Co. in Berlin, N. H. About twenty yards from the crib a gigantic boulder punctuated the riffle creating a downstream V. The phantom resided twelve feet or so off the boulder towards the crib side of the river.

Then I noticed him. He was a lean man with a walnut creased and colored face. He had a khaki Army shirt on, a felt crusher hat, and green woolen pants. His right sleeve was pinned up, a phantom salute.

“Who’s that, Gramp?”

“That’s Bill Bryant, a famous Magalloway guide.”

“What happened to his arm?”

“Lost it, I think, in W. W. I.

“What makes him famous?”

“Well, besides being cantankerous, he knows these woods and waters better than anyone. You could take him blindfolded on a starless night to any spot on this river and he could tell you by its sound where you were and where the big fish would be.. yep, and he has no liking for outsiders, flat landers he calls them. Why once he came upon a New Jersey fisherman who was wading in the river. When the fisherman saw Bill’s guide patch he asked for directions to the Gravel Bank Pool. Bill told him the information would cost five dollars. The outsider thought the price was steep, but paid it nevertheless. “0. K.,” the Jersey fisherman asked, “where’s the pool?” Bill replied, “You’re standing in it.”

“Wasn’t the guy angry, Gramp?”

“Not for long; not after he found out it was Bill Bryant. Bill’s reputation always preceded him.”

The next week’s catch at the Landing Pool included two six inch trout and three large river fall fish. The phantom was gone as far as we knew. Perhaps it had tired of tantalizing us.

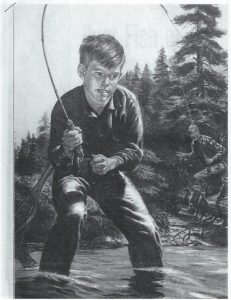

I was fishing now in Gramp’s spot; I would not be challenged by the silvery leviathan. I had an observer, though. Up on the bridge looking down at me was Bill Bryant. He walked slowly, crossed the wire guardrail, descended the grassy slope, and sauntered up to my left side. I worked my seven and one-half foot L.L. Bean glass rod as well as I could. The H-C-H line glided out thirty feet. the fly flicking off water at the end of the nine foot tapered leader.

“Is that as far as you can cast, sonny?”

“Huh?”

“You don’t know how to cast much; let me show you.”

Simmering, I handed the rod over to the one-armed man. “Go ahead, old codger,” I said to myself, “show me something.”

Four or five false casts later my fly hit the grass on the other side of the river. Mr. Bryant’s casting was flawless. How he managed his chin, teeth, and arm to this day is a mystery to me. It seemed the line, leader, and fly had such an aversion to his gruffness that by their own volition they left the rod as easy as a final exhalation.

“There, sonny, that’s how. Now, let me see your wet flies.”

I reeled in, tucked the rod under my arm, and pulled out a fleece wallet where I kept streamers and wets.

“Huh! You don’t have the right ones, but this number fourteen Professor might work if you’re up to casting twelve more feet to the fording rock.”

“What fording rock?”

“That one out there; the only one exposed hereabouts. We called it that before the bridge. Wagons could cross the river here safely when that was exposed six or so inches. Now you want to cast a foot or two into the eddy behind the rock, lower the rod tip, and let the fly drift downstream. Don’t move the fly. When it reaches the end of the drift, twitch it in slowly. And be ready.”

Damn but I tried. Six casts and I was still short by two feet. This is it I thought. I can’t let a one-armed man show me up, and I’m not going to allow his sarcasm to beat me. My final cast was part skill and will. My body quivered with the line’s release, and the fly hit the water just where he told me it should. But what about other instructions?

“Don’t move that fly!” he exhorted.

As the fly drifted below me, Gramp came into my line of sight some forty yards downstream.

“Now! Twitch the fly!”

What happened next I’ve replayed for years. The water erupted at my fly’s location and simultaneously a jolt hit my wrist as the rod doubled. Gramp looked up at the sound of my yelling and the whining aluminum reel. The phantom salmon slashed downstream, porpoising twice. Then the tippet broke.

“I told you so, sonny. Too bad. That was a big fish, six or seven pounds. Ah, well,” he said patting my back, “life’s lessons.”

Mr. Bryant walked up the hill, across the bridge to his car, and out of my life forever. I never saw him again, but he, my grandfather, and those other Magalloway guides whom I knew are now the phantoms who fish with me and teach me the lessons learned on the Magalloway many years ago in the shadows of Aziscoos Mountain.

Gifford Stevens, a high school teacher and craftsman, is a resident of Bradley.

For more articles and stories about hunting, fishing and the outdoors, be sure to subscribe to our monthly publication the Northwoods Sporting Journal.

To access past copies of the Northwoods Sporting Journal in digital format at no charge, click here.